“People should help those who help them” – Alvin Gouldner *

Gouldner, a social scientist, was not laying out a moral commandment in the above statement, but rather referring to the demand made by a fundamental social norm, one that is subscribed by all human societies known to us – the norm of reciprocity. This is a unwritten, unspoken “rule” that demands that we must give, in fair value, what we have received from another. If someone lends you money, you should lend them money when they are in need. If someone gives you an expensive gift on your birthday, you should give them something expensive on their birthday. If someone invites you to dinner, you will feel obliged to invite them to dinner sometime. The norm arises from the principle of fairness, and as human beings we are conditioned to feel obliged to return favours that we receive.

Just as we feel obliged to return favours, we also feel obliged to return “self-disclosures”. That is, when someone shares some personal information about themselves, we are likely to find ourselves revealing personal information about ourselves to them. For example, if you happen to be in a long train journey and the person next to you tells you about his employment, you might find yourself in an awkward situation if you don’t feel willing to tell him about your job (or, if you are unemployed, the lack of it). The reciprocation of self-disclosures has been studied fairly extensively in social science and social psychology. When it comes to personal information, people do indeed tend to give back depending on what they get.

With the advent of the internet, online social networking and other communication technologies that are fundamentally changing how we socialize and interact, a question that arises is: how does reciprocity affect the way we disclosure personal information to each other in the online medium? The first basic question is, do people reciprocate at all the disclosure of personal information at all when they interact online? Further, most of the prior work on the reciprocity of disclosure is in the context of face to face interactions. One assumption in such work, that often does not hold in online interactions, is that such disclosures take place in directed one-to-one interactions. However, in online social networks today, people often disclose through broadcast channels, such as on profile pages or wall posts. What stands out about these disclosures in comparison to face-to-face interactions is that these disclosures are often not directed to any individual in particular, they are simply broadcast to a large audience. So the question is, do such broadcast disclosures also bring the reciprocity norm into play? In other words, if I disclose some personal information on my profile page, that is directed to nobody in particular, and then I ask somebody for their personal information, are they going to see it as fair for them to give me this information because I revealed mine, although not directly to them?

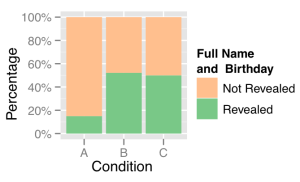

In order to answer these questions, we conducted a simple experiment. We logged into user profiles on Livemocha, a language learning social network where interactions are typically between people who have never met before, and attempted to elicit the full name and date of birth, in other words some simple personal information, from other users. These user profiles were fictitious and created solely for the purpose of running this experiment. We attempted to elicit this information by sending them a private message and asking them for it in the pretext of being interested in their culture. However, we used 3 different approaches to go about this. For the first group of users (condition A), we merely asked them for this information without giving out any personal information of the fictitious profile. For the second group of users (condition B), the fictitious profile revealed his own full name and date of birth in the private message. For the third group of users (condition C), the fictitious profile did not reveal any personal information in the private message to the users, but revealed this information on his public profile page. In other words, the profiles used for this group of users shared their personal information in a broadcast manner, not directed to anyone in particular. Thus, the purpose of this approach was to test whether broadcast disclosures also bring the reciprocity norm into play.

As we suspected, the second group of users, to whom the fictitious profile shared his full name and date of birth in the private message, was significantly likelier to share their own information with the fictitious profile than the first group of users, who were not given any personal information from the fictitious profile. In other words, this confirms that individuals do reciprocate the sharing of this kind of personal information in online interactions. What is even more interesting was that even the users in the third group, those with whom the fictitious profile did not share this information in the private message but had rather shared this in his public profile page, were more likely than the users in the first group to share their own information with the fictitious profile. Further, we found no significant difference between users in the second group and those in the third group in terms of their likeliness to share this information. In other words, we found that users were just as likely to reciprocate the sharing of this kind of information irrespective of whether the information was given to them in a private, one-to-one message or was shared publicly in a broadcast manner, which they were able to view.

The results of our experiment shed light on the “give and take” dynamics of personal information sharing in online interactions. Since we are talking about personal information here, this has implications for online privacy and security. The experiment demonstrates the potential vulnerability of users against attempts to trick them into revealing information by exploiting this social norm. Inferring or linking personal information such as that obtained in the current study would typically be an important first step in a malicious party’s attempt to exploit a user. For example, the malicious party might use elements of context inferred from the site such as the user’s interest in learning a language or the people that the individual has friended in the social network. The unsuspecting user might then be sent a spam message or email incorporating these elements of context on his birthday for an advertisement of a language learning product or even a link to a virus. Such context-aware spam messages are known to have higher click-through rates and are thus likelier to trick the user.

With people increasingly interacting with strangers on various social networking platforms, an important research challenge is to develop an understanding of how social mechanisms and norms can be exploited for potential attacks. Such an understanding can aid designers of social networking sites to foresee these potential attacks and put design mechanisms in place to prevent them. Systems must support the development of ties between individuals, and mutual disclosure of personal information is an integral component of such a bonding process. However, users need to be able to distinguish between genuine individuals forming a relationship and malicious parties. The challenge is then to provide mechanisms that help users identify such malicious parties in a manner that does not hinder the sharing of information between genuine users. Understanding these social mechanisms paves the way for us to then think about how to address these potential threats and facilitate users to fulfill the needs that they seek to fulfill through these social networks.

* In Gouldner, A. W. (1960). “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.” American Sociological Review 25: 161-178.

Publication

[bibtex key=Venkatanathan:InteractingWithComputers:]